Naples

© Paolo Patrizi

Jubilant Rome

©Paolo Patrizi

For years Italians had assumed that although Sicily and much of the south were prey to the mafia, their beautiful capital was much less vulnerable. Recent events have shown that comforting vision to be wrong on two counts. Italy’s southern mafias have been quietly building stakes in the capital’s economy, and Rome has been revealed to host an autonomous underworld more extensive, organised and powerful than anyone knew. Rome is the real money-laundering centre for the money earned from drug trafficking, arms, extortion, illegal money lending and prostitution. Another new, quasi-mafia group named the Mafia Capitale, consisted of crooked businessmen, politicians and officials, has been active in the capital, skimming hundreds of millions of euro off everything from road maintenance to migrant accommodation centres. This situation has its roots in the immensely degraded political and religious culture of the leadership, that mirrors a far too low level of acculturation amongst the population.

Plastic on tree branches, Tiber river banks, Rome, Italy

Trees along the Tiber are covered in plastic bags and other rubbish every time the river overflows

The Plastic Tide

Plastic washed ashore on a beach in the proximity of Rome “Leonardo da Vinci” Airport

Washed out on our coasts, the plastic pollution spectacle blatantly unveiling on our beaches is only the prelude of the greater story that unfolds further away in the world’s oceans, yet mostly originating from the land we stand on.

It is estimated that 8.8 million metric tons of plastic waste is dumped in the world’s oceans each year. A lot of plastic debris in the ocean breaks down into smaller pieces, it is ingested by marine life, and it is thought that a significant amount sinks to the seabed. But a lot of it just floats around, accumulate at the center of gyres and on coastlines, frequently washing aground.

A wide variety of anthropogenic artefacts can become marine debris; bottles, plastic bags, fishnets, clothing, lighters, tires, polystyrene, containers, plastics shoes and various wastes from cruise ships and oil rigs are among a myriad of man-made items commonly found to have washed ashore, all sharing a common origin: us.

A walk on a beach, anywhere, and the plastic waste spectacle is present. All over the world, the statistics are growing, staggeringly. Tons of plastic that can vary in size are discarded every year, everywhere, polluting lands, rivers, coasts, beaches, and oceans.

The plastic waste tide we are faced with is not only obvious for us to clearly see washed up on shore or floating at sea. Most disconcertingly, the overwhelming amount and mass of marine plastic debris are made of microscopic debris that cannot be just scooped out of the ocean. They are not absorbed into the natural system, they just float around within it, and ultimately are ingested by marine animals and zooplankton. This plastic micro-pollution, with its inherent toxicity, bears grave consequences on the food chain.

© Paolo Patrizi

Hiwatari-sai

Takaosan Yakuoin Temple is an old Buddhist temple located atop Mt. Takao and is known as one of three central temples of Shingon sect, Chisan division in the Kanto region. The fire-walking festival is one of the traditional events held at Yakuoin Temple. At the festival, believers first pray for the safety of family, traffic and body and then follow Yamabushi (Shugendo practicing monks) to walk barefoot over the sacred goma fire that is smoldering and still partially burning. The sight of yamabushi monks bravely walking through the flame while chanting brings the event’s highlight.practicing monks) to walk barefoot over the sacred goma fire that is smoldering and still partially burning. The sight of yamabushi monks bravely walking through the flame while chanting brings the event’s highlight.practicing monks) to walk barefoot over the sacred goma fire that is smoldering and still partially burning. The sight of smoldering and still partially burning. The sight of yamabushi monks bravely walking through the flame while chanting brings the event’s highlight.practicing monks) to walk barefoot over the sacred practicing monks) to walk barefoot over the sacred goma fire that is smoldering and still partially burning. The sight of smoldering and still partially burning. The sight of yamabushi monks bravely walking through the flame while chanting brings the event’s highlight.

© Paolo Patrizi

Urban Shrinkage

Japan

© Paolo Patrizi

In view of a recently shrinking population and the decline of peripheral rural regions in favour of the large metropolises Tokyo and Osaka, urban shrinkage in Japan, is primarily the result of demographic transition. As a country with a high life expectancy, a low birth rate, and negligible immigration, Japan is not only exemplary for the consequences of an aging population, for the past several years it has registered an overall population decrease. The shrinking of the population in the peripheral rural areas of Japan and the problems that will face the whole country in the long term are already a reality: dramatic declines in population, the extreme aging of society, and problems of maintaining a sustainable infrastructure. The population concentration in Japan, as elsewhere, is primarily a consequence of industrialization. The escape from the countryside which begun at the turn of the twentieth century was motivated by an excess of workers in small-farm agriculture, and initially it had many positive effects. The personnel reductions in traditional family operations provided impetus for agriculture to improve efficiency and labour productivity and at the same time provided a welcome source of labour for industry. As industrialization increased during the post-war period, the motivations and effects of domestic migration changed. The more the economic upswing influenced urbanization processes and the attractiveness of cities, the more clearly it changed from a push effect of the rural areas to a pull effect of the city. The concentration of population and the overdevelopment of agglomeration areas went hand in hand with thinning and underdevelopment in the rural and peripheral regions. This trend, which was particularly strong during the face of greatest economic growth, between 1955 and 1973, has clearly weakened since the mid-1970s, but it has nevertheless continued to worsen the imbalance in regional population distribution. A more refined examination of urban development in rural and peripheral regions, shows that shrinking is almost always associated with deindustrialization and the aging of society. At the centre of the problem of population aging in Japan is the family. Like other Asian societies that have been heavily influenced by the strong emphasis on filial piety associated with Confucian philosophical tradition, Japanese have historically viewed co-residence with parents as a moral obligation of at least one child (in Japan has normally been the eldest son), and a corresponding focus on provision of care to frail elderly by a family member. However, in the post-World War II era, some of these assumptions have come to be challenged as Japan has become increasingly urbanized and mobile, and as interpretations of values in other societies (particularly the U.S.) have influenced how Japanese think about individual and collective roles in society. The rapid change which Japan has experienced since the end of the World War II, and particularly since the end of the bubble economy of the 1980s, has had a significant influence on the elderly. As young people have moved to major metropolitan areas, the elderly have been effectively left behind in the countryside. Over the next few years, we will see the increased aging of the population of Japan, a process that will be magnified in rural areas, leaving neighbourhoods and in very remote areas whole towns with no young people and children.normally been the eldest son), and a corresponding focus on provision of care to frail elderly by a family member. However, in the post-World War II era, some of these assumptions have come to be challenged as Japan has become increasingly urbanized and mobile, and as interpretations of values in other societies (particularly the U.S.) have influenced how Japanese think about individual and collective roles in society. The rapid change which Japan has experienced since the end of the World War II, and particularly since the end of the bubble economy of the 1980s, has had a significant influence on the elderly. As young people have moved to major metropolitan areas, the elderly have been effectively left behind in the countryside. Over the next few years, we will see the increased aging of the population of Japan, a process that will be magnified in rural areas, leaving neighbourhoods and in very remote areas whole towns with no young people and children.

The flip side of the well-known hymn to economic success.

Tokyo

The Japanese construction industry generates unemployed workers which factor has led to an increase in the number of homeless people.The story of day-labourers, is, in fact, the flip side of the well-known hymn to economic success.The vast majority are engaged in construction and the contracting firms, taking advantage of an extremely fluid labour supply, have the ability to keep as many workers as possible off the payrolls, using them on as-needed bases. Without this intricate system, lifetime employment and other corporate benefits of the good life at the top would be far less secure.

© Paolo Patrizi

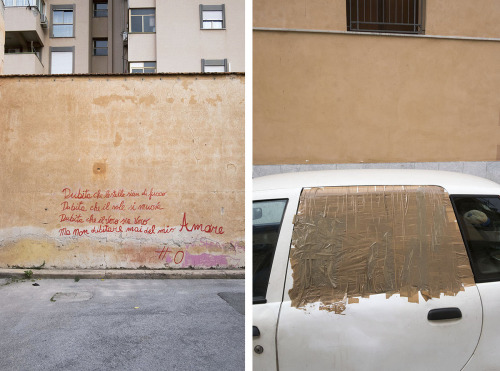

Palermo

© Paolo Patrizi

“Rights Without Borders”

People march in a national demonstration for the rights of migrants on December 16, 2017, in Rome, Italy

© Paolo Patrizi

Nigerian girls who hawk sex on the streets of Italy

© Paolo Patrizi

For nearly three decades, a thriving sex-trafficking industry has been operating between Nigeria and Italy. Many experts believe the trade in women started in the 1980s when Nigerians travelling to Italy on work visas to pick tomatoes realised that selling sex was far easier and more profitable than harvesting fruits or vegetables.

Since then an estimated 30,000 Nigerian women have been trafficked from their home country into prostitution, finding themselves on street corners and brothels in Italy and other European states.

More than 85% of these women have come from Nigeria’s Edo state in the south of the country, where traffickers have historically exploited chronic poverty, discrimination, a failing education system and lack of opportunities for young women to sell false promises of prosperity in Europe.

World Food Day

This year’s World Food Day takes the theme of migration and the need to invest in food security and rural development so that people are no longer forced to uproot their lives. Three-quarters of the extreme poor base their livelihoods on agriculture or other rural activities. Creating conditions that allow rural people, especially youth, to stay at home when they feel it is safe to do so, and to have more resilient livelihoods, is a crucial component of any plan to tackle the migration challenge. By investing in rural development, the international community can also harness migration’s potential to support development and build the resilience of displaced and host communities, thereby laying the ground for long-term recovery and inclusive and sustainable growth.

© Paolo Patrizi

Aẓān, Railway Station Underpass, Italy

© Paolo Patrizi

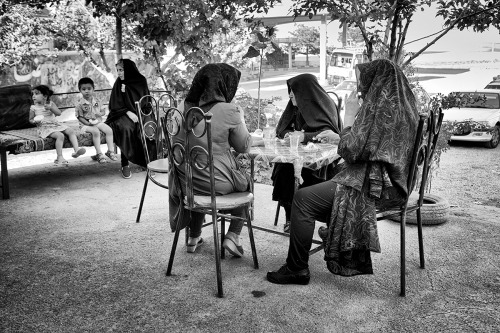

Constantinople

Coffee & Raki

© Paolo Patrizi

Colourful Mountains -آلا داغلار

East Azerbaijan Province, Iran

© Paolo Patrizi

Urmia Lake - دریاچه ارومیه

© Paolo Patrizi

In the late 1990s, Lake Urmia, in north-western Iran, was twice as large as Luxembourg and the largest salt-water lake in the Middle East. Since then it has shrunk substantially, and was sliced in half in 2008, with consequences uncertain to this day, by a 15-km causeway designed to shorten the travel time between the cities of Urmia and Tabriz.

Historically, the lake attracted migratory birds including flamingos, pelicans, ducks and egrets. Its drying up, or desiccation, is undermining the local food web, especially by destroying one of the world’s largest natural habitats of the brine shrimp Artemia, a hardy species that can tolerate salinity levels of 340 grams per litre, more than eight times saltier than ocean water. Effects on humans are perhaps even more complicated. The tourism sector has clearly lost out. While the lake once attracted visitors from near and far, some believing in its therapeutic properties, Urmia has turned into a vast salt-white barren land with beached boats serving as a striking image of what the future may hold.

Desiccation will increase the frequency of salt storms that sweep across the exposed lakebed, diminishing the productivity of surrounding agricultural lands and encouraging farmers to move away. Poor air, land, and water quality all have serious health effects including respiratory and eye diseases .

The results of an investigation, which recently appeared in the Journal of Great Lakes Research, revealed that in September 2014 the lake’s surface area was about 12% of its average size in the 1970s, a far bigger fall than previously realised. The research undermines any notion of a crisis caused primarily by climate changes. It shows that the pattern of droughts in the region has not changed significantly, and that Lake Urmia survived more severe droughts in the past.